CXI Overview

CXI Full Name

Coherent X-ray Imaging Instrument

Short Description

The Coherent X-ray Imaging (CXI) instrument (Liang et al. J. Synchrotron Rad. 22 (2015)) makes use of the unique brilliant hard X-ray pulses from LCLS to perform a wide variety of experiments utilizing various techniques. The primary capability of CXI is to make use of the high peak power of the focused X-ray beam using the “diffraction-before-destruction” method. This technique prevents damage to a sample during the measurement by acquiring the data faster than the damage or destruction process with ultrashort pulses. CXI has hosted experiments for many scientific fields, including structural biology, materials science, materials in extreme conditions, atomic molecular and optical physics, chemistry, soft condensed matter and high field X-ray science.

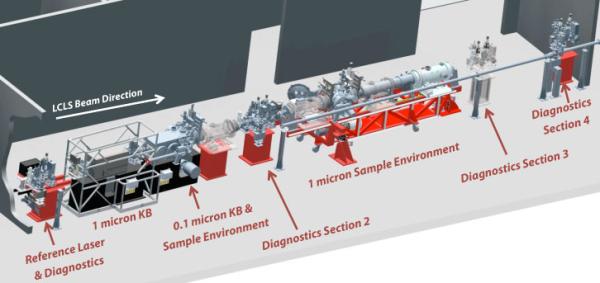

The CXI instrument consists of a highly flexible instrumentation suite to make use of hard X-rays primarily in a vacuum sample environment. A variety of tools and devices allow CXI to make use of other techniques such as X-ray Emission Spectroscopy, back-scattering, small and wide angle scattering, ion and electron time of flight spectroscopy.

A flexible pump laser system is available for time-resolved experiments in the femtosecond time scale. Samples can be introduced to the X-ray beam either fixed on targets or in a liquid jet. Experiments at atmospheric pressure are possible under certain limited circumstances. High quality Kirkpatrick-Baez focusing optics are available to generate three foci (10, 1 and 0.1 micron) in the 5-11keV range. Photon energies greater than 11keV can be used by focusing with compound refractive lenses to a focal size of >2 microns.

Diffraction Before Destruction

X-ray diffraction has long been used to determine atomic structure. The X-ray dose needed to achieve a given resolution for a particular sample can be calculated. It can be shown that the dose required to image a single biological molecule is much larger than the dose required to completely destroy the molecule through radiation damage processes. X-ray crystallographers mitigate this problem by spreading the damage over billions of molecules in a single crystal, greatly enhancing the diffraction signal. Since the molecules are all identical and precisely aligned in the crystal, the X-ray scattering information is preserved and the structure can be determined.

LCLS offers another way around the damage problem. Since the FEL X-ray pulse is very intense and very short, it is possible to deliver the required dose to a sample and record the scattered X-ray information before the damage processes have time to destroy the sample. In other words, an LCLS X-ray pulse can be focused onto a single molecule, which gets destroyed – but not before the scattered X-rays are already on their way to the detector carrying the information needed to deduce the image. The Coherent X-ray Imaging (CXI) Instrument offers the possibility of determining structures at resolution beyond the damage limit for samples which do not form large crystals, including important classes of biological macromolecules.

CXI aims to provide a flexible suite of instrumentation for “diffract-before-destroy” studies, but also suite for other techniques, such as laser pump/X-ray probe methods and a variety of scattering and spectroscopy techniques. Scientific fields such as material science, materials in extreme conditions, atomic molecular and optical physics, chemistry, soft condensed matter and high field X-ray science have and will find applications at CXI.

Scientific Programs

Often, large crystals of a certain protein cannot be grown but a large number of very small crystals can readily be obtained. These sub-micron crystals do not scatter enough X-rays to yield an atomic structure using conventional protein crystallography techniques. The high flux of LCLS could allow these to be used for structure determination. This high flux/short pulse duration also has the advantage of allowing in principle damage-free higher resolution of radiation-sensitive samples such as metalloenzymes for example. Assuming all the nanocrystals possess the same crystal symmetry, a series of nanocrystals can be illuminated by LCLS X-ray pulses and the diffraction patterns recorded. A full 3D set similar to conventional protein crystallography can be assembled from many small crystals to determine the protein structure. The nanocrystals can be delivered into the CXI beam using a liquid jet (Weierstall et al. Rev. Sci. Instrum. (2010)), LCP jet (Weirstall et al. Nature Communications (2014)), an electrospinning jet (Sierra et al, Acta Cryst D (2012)) or mounted to a suitable substrate in vacuum (Frank et al. IUCrJ (2014)). The liquid jet options provides high data rate while the substrate mounting and LCP jet can help minimize sample consumption.

Small crystals also benefit kinetics and dynamics studies due to the higher activation fraction in small crystals. For both optically excited systems where penetration through the sample can limit the photoactivated yield and mix-and-inject systems where a substrate must diffuse through the crystal, small crystals are advantageous.

The CXI instrument is an in-vacuum high peak power instrument using hard X-rays. The vacuum environment provides extremely low background scattering which benefits gas phase samples. With proper alignment, the background can be less than a photon/data frame. Along with the ability to utilize higher photon energies and CXI’s short pulse UV laser capabilities, it provides an ideal environment to perform gas phase chemistry experiments – i.e. molecular movies that image chemical reactions in real time.

The CXI instrument is primarily an in-vacuum high peak power instrument using hard X-rays. This makes CXI the ideal home for AMO science that requires the use of X-rays above 4-5 keV. Time-of-flight spectrometers and photon detectors can be added to the CXI sample chambers to allow AMO studies.

The LCLS source produces hard X-ray fields of unprecedented high intensity. It allows for the first time tests of radiation damage models under such extreme conditions as well as tests of fundamental X-ray physics under extreme fields. These models are directly relevant to atomic-resolution imaging since the damage suffered during a pulse must be limited or the image reconstruction will suffer. The interaction of the powerful LCLS pulses with solid matter can be studied using the CXI instrument under unique extreme conditions using high-quality focusing optics.

It is possible, with the use of an optical pump laser, to obtain dynamic information of photo-induced changes in non-crystalline and crystalline samples with sub-picosecond time resolution. A flexible pump laser system (nanosecond and femtosecond lasers) is provided at the CXI instrument to allow a wide range of dynamics studies.

LCLS makes it possible to obtain two-dimensional projections of any non-reproducible nanoparticle and three-dimensional images of reproducible objects using the diffract-the-destroy technique. Furthermore, the CXI beam can be attenuated to a level slightly below the damage threshold of an inorganic nanoparticle and a full 3D reconstruction can in principle be obtained from a single particle using multi-image tomographic techniques. The transverse coherence length of the CXI beam can allow small particles to be imaged in 3D at high resolution.

The ultrashort pulses of LCLS open new possibilities to study short lived states of matter in extreme conditions. These extreme or transient states can be created with a pump laser and then probed with high time resolution with LCLS pulses using diffraction (Milathianaki et al. Science (2013)), scattering or in principle emission techniques.

Only a two-dimensional diffraction pattern can be collected from a single biomolecule before it is destroyed by the LCLS beam. Such a two-dimensional pattern encodes information about a projection image of the object onto a plane parallel to the detector. Three-dimensional structural information about highly-reproducible molecules such as viruses, large proteins or molecular complexes can be derived if a series of the molecules is delivered into the LCLS beam one after the other. Each molecule would have a different orientation and a full 3D diffraction data set can be obtained from a large number of identical copies of the sample. In theory, it could be possible to obtain high resolution structures for difficult to crystallize biomolecules. Research and development is required to demonstrate this capability.

Examples of Experimental Geometries and Techniques at CXI

Serial Femtosecond Crystallography (SFX)

Using a Lipidic Cubic Phase Jet

- Wei Liu et al. "Serial Femtosecond Crystallography of G Protein–Coupled Receptors" Science 342 1521 (2013)

Using a Gas Dynamic Virtual Nozzle

- Sébastien Boutet et al. "High-Resolution Protein Structure Determination by Serial Femtosecond Crystallography" Science 337 (6092) 362 (2012)

- Lars Redecke et al. "Natively Inhibited Trypanosoma brucei Cathepsin B Structure Determined by Using an X-ray Laser" Science 339 6116 (2012)

Using an Electrostatic Jet

- Raymond G. Sierra et al. "Nanoflow electrospinning serial femtosecond crystallography" Acta Cryst D68 1584-1587 (2012)

Emmission Spectroscopy Simultaneously with SFX

- Jan Kern et al. "Simultaneous Femtosecond X-ray Spectroscopy and Diffraction of Photosystem II at Room Temperature" Science (2013)

Experimental Phasing of SFX Data

- Thomas R. M. Barends et al. "De novo protein crystal structure determination from X-ray free-electron laser data" Nature 0 (2013) doi: 10.1038/nature12773

2D Crystallography

- Matthias Frank et al. "Femtosecond X-ray diffraction from two-dimensional protein crystals" IUCrJ (2014)

Shock Dynamics

- D. Milathianaki et al. "Femtosecond Visualization of Lattice Dynamics in Shock-Compressed Matter" Science 342 6155 (2013)

CXI TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS

CXI CONTACT INFO

Meng Liang

CXI Instrument Lead Scientist

(650) 926-2827

mliang@slac.stanford.edu

Sandra Mous

Scientist

(650) 926-6225

smous@slac.stanford.edu

Andy Aquila

Scientist

(650) 926-2682

aquila@slac.stanford.edu

Michael Minitti

Scientist

(650) 926-7427

minitti@slac.stanford.edu

Kirk Larsen

Laser Scientist

(650) 926-3728

larsenk@slac.stanford.edu

Joe Robinson

Laser Scientist

(650) 926-5190

jsrob@slac.stanford.edu

Matt Hayes

Area Manager

(650) 926-3060

hayes@slac.stanford.edu

Kelsey Banta

Science and Engineering Associate

(650) 926-3819

banta@slac.stanford.edu

Serge Guillet

Mechanical Engineer

(650) 926-4771

sguillet@slac.stanford.edu

Divya Thanasekaran

Controls Engineer

(650) 926-8917

divya@slac.stanford.edu

Stella Lisova

Sample Delivery

(650) 926-3272

stellal@slac.stanford.edu

Philip Adam Hart

Detectors

(650) 926-2813

philiph@slac.stanford.edu

CXI Control Room

CXI Hutch

(650) 926-6291

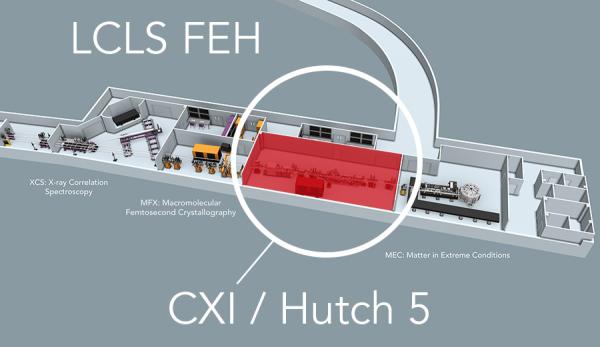

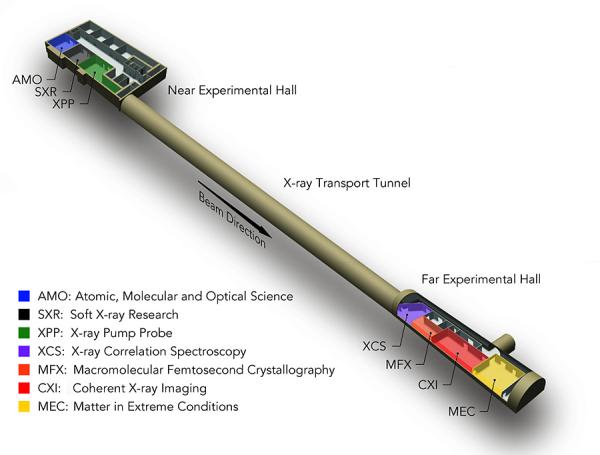

CXI LOCATION