XPP Experimental Methods

Dynamics of Photo-induced Phase Transitions

Optical manipulation of solids can lead to photo-induced phase transitions on the ultrafast time scale. For many of these materials, a change in crystal symmetry accompanies a magnetic, ferroelectric, or metal-insulator phase transition. These materials have the potential to be utilized as ultrafast switches in magnetic and electro-optic devices and time-resolved X-ray crystallography provides an ideal tool for tracking the changes in atomic structure. For those systems that undergo a 1st-order photo-induced phase transition, time-resolved X-ray scattering has the potential to provide information about the structure and size of the new phase nucleus with previously unachievable detail.

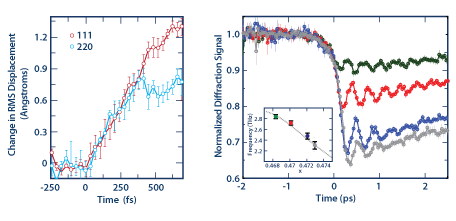

Studies of Intense Laser-matter Interactions

The structural response of materials to femtosecond laser excitation differs fundamentally from the response to excitation with longer pulses, because the generation of carriers by linear and nonlinear absorption occurs faster than the time scale for carrier diffusion and carrier-phonon scattering. Consequently, the photon field can deposit enormous quantities of energy into electronic degrees of freedom, while the vibrational internal energy remains comparatively unperturbed. Excitation of carriers can alter the ionic potential energy landscape of a material and can lead to atomic motion [1,2] (see Figure 1). Identifying the important distinctions between materials and further correlating the material response with material electronic structure remains an important objective for understanding the light-matter interaction. Further knowledge in this field will enhance our ability to manipulate and control material structure with light.

Time-resolved Studies of Chemical Dynamics in Solution

The majority of chemical reactions in biological, environmental, and industrial settings occur in disordered media, with liquid water being the ubiquitous example. The development of methods for studying ultrafast time-resolved diffuse scattering in liquids will be an important component of the LUSI project. Pioneering diffuse scattering experiments have been conducted at ID-9 at the ESRF [3]. While these studies have demonstrated the viability of transient diffuse scattering measurements in liquids, the technique when applied at a synchrotron has insufficient time resolution for studying chemical dynamics. For these studies the improved time resolution of the LCLS will provide a significant advantage over synchrotron facilities.

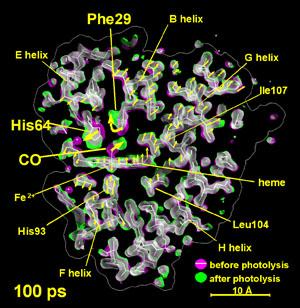

Dynamics of Photoactive Proteins

From Schotte et al., Science 300:1944 (2003). Reprinted with permission from AAAS.*

The variability and efficiency of proteins make them powerful molecular foundries. The size, diversity and complexity of proteins also make them challenging to study and understand with atomic detail. X-ray crystallography helped launch the molecular biology revolution and maintains a position of unique prominence in structural biology as the most powerful tool for determining biomolecular atomic structure. While enormously useful, the equilibrium structure cannot capture the full chemical significance of a protein. To understand how a protein functions at a mechanistic level of detail requires measuring in real time the nuclear motion that accompanies its function. Time-resolved protein crystallography represents the most powerful tool for achieving this experimental objective. While time-resolved crystallographic measurements have been conducted with time resolution as short as 150 ps, Figure 2 demonstrates that global structural changes have already occurred at the earliest time delay [4]. To observe and understand how a local perturbation propagates from the epicenter of the distortion to points far removed will require X-ray pulse durations and amplitudes only achievable with linac-based sources. By extending the time resolution of these measurements into the femtosecond regime, the ability to observe how a local distortion can be channeled into a concerted global structural change will be possible for the first time.

References

- A. M. Lindenberg et al., Science, 308, 392-395 (2005).

- D. M. Fritz et al., Science, 315, 633-636 (2007).

- H. Ihee, M. Lorenc, T. K. Kim, Q.Y. Kong, M. Cammarata, J. H. Lee, S. Bratos and M. Wulff, Science, 309, 1223-636 (2005).

- F. Schotte, M. Lim, T. A. Jackson, A. V. Smirnov, J. Soman, J. S. Olson, G. N. Phillips, M. Wulff and P. A. Anfinrud, Science, 300, 1944-1947 (2003).

XPP CONTACTs

Takahiro Sato

XPP Instrument Lead

(650) 926-3749

takahiro@slac.stanford.edu

Adam White

Area Manager

(650) 926-4778

adamwh@slac.stanford.edu

Roberto Alonso-Mori

Spectroscopy Scientist

(650) 926-4179

robertoa@slac.stanford.edu

Diling Zhu

Methologist/X-ray Optics Scientist

(650) 926-2913

dlzhu@slac.stanford.edu

Matthieu Chollet

Staff Scientist

(650) 926-3458

mchollet@slac.stanford.edu

Sanghoon Song

Staff Scientist

(650) 926-2255

sanghoon@slac.stanford.edu

Yanwen Sun

XPCS/X-ray Optics Scientist

(650) 926-2562

yanwen@slac.stanford.edu

Hasan Yavas

IXS /RIXS Scientist

(650) 926-3084

yavas@slac.stanford.edu

Matthias Hoffmann

Laser Scientist

(650) 926-4446

hoffmann@slac.stanford.edu

Ying Chen

Mechanical Engineer

yingchen@slac.stanford.edu

Vincent Esposito

Controls & DAQ Engineer

(650) 926-3410

espov@slac.stanford.edu

XPP Control Room

(650) 926-1703

XPP Hutch

(650) 926-7463